During Diversity Month, the Garden is sharing stories of people, their relationship with plants and the important role diversity plays for both.

It may not seem so obvious to urban dwellers, but throughout history, people and the plants they live among have been intimately connected. A diversity of plants is essential for human survival particularly when their environment is downright hostile.

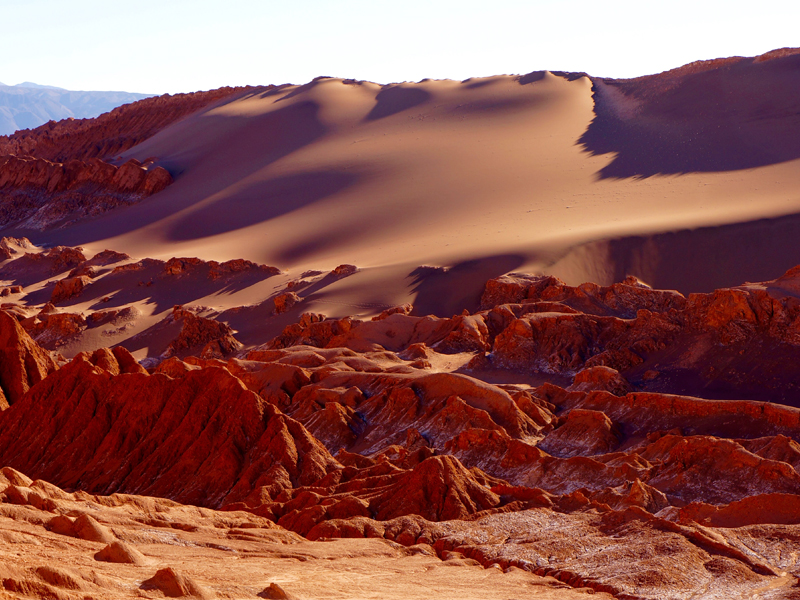

The Atacama Desert in South America is one of those hostile environments. It is the driest desert on earth, stretching more than 2,000 miles along the coasts of southern Peru and northern Chile. Over its entirety, the Atacama receives an average of just a half-inch precipitation per year. Survival there requires all forms of life to be incredibly adaptable and resilient.

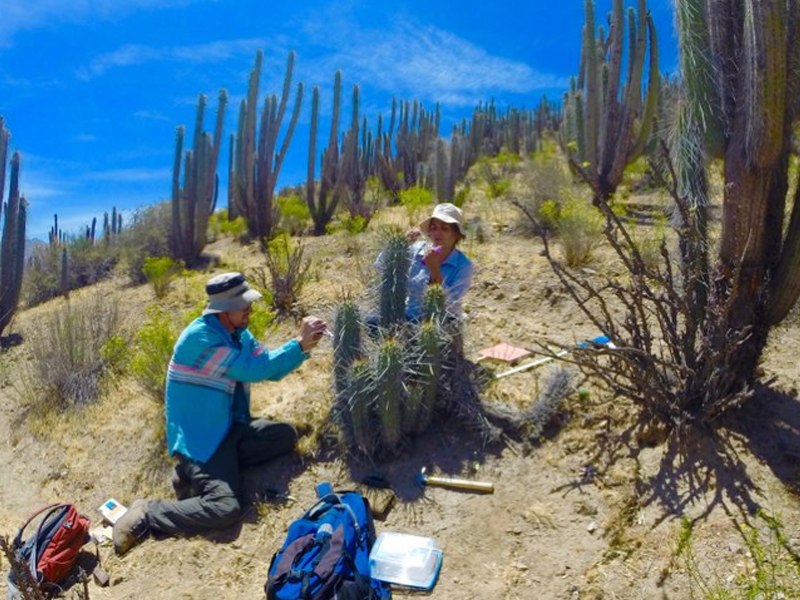

In 2018, Garden researchers, Raul Puente and Kevin Hultine travelled to Vicuña, Chile to learn from the Atacama’s extreme conditions, and from its plants and people. They set up study sites to research the potential impacts of climate change on one of that desert’s largest cactus species, Eulychnia acida. Known by local people as the copao, the massive cactus resembles the multi-armed organ pipes of the Sonoran Desert. The copao grow at elevations where there is absolutely no rainfall. Because they are so exceptionally well adapted, they survive on the only moisture available–coastal fog.

The people of the Atacama have persisted for thousands of years by cultivating edible plants they could and by using the native copao cactus for its nutritious fruit and wood. Local people explained to Puente how they harvest the copao fruit in October using sticks made from cactus wood. They knock the fruit from tall stems and eat them fresh, make them into an acidic marmalade and even use them as shampoo. Local people also use the dried, hollow stems to make rain sticks, a popular item sold in gift shops.

The current economy in this region of Chile centers on cultivating vineyards and processing grapes into pisco, an alcoholic beverage. A more modern use of the tart copao fruit is as a mixer in the popular pisco sour cocktail. Though the grape-growing industry provides local people with jobs, it also requires clearing the desert of native plant life. As more vineyards are planted, the copao’s habitat will shrink along with its population. To improve the copao’s odds, Chilean collaborators are researching ways to domesticate this incredible native cactus and protect them from potential loss.

Closer to home in the southern Sonoran Desert, the copao’s look-alike cactus, Stenocereus thurberi, (aka organ pipe) commands the landscape. Its Spanish name is pitaya and they grow in a large range of habitats from southwestern Arizona, to 500-plus miles south to the Mexican state of Sinaloa and the southern Baja peninsula. They are one of only three cactus species in the world considered so special that a national preserve was established for their protection. In less arid regions of Sonora, pitayas can grow 30 to 40 feet high and develop hundreds of arms.

Pitayas have played an important role in the lives of many native peoples but have been particularly essential to the Mayo and Yaqui of Sonora’s southern coastal plain. Throughout history, people in small villages built their homes and fences using the dried wood of pitayas. Before barbed wire became available in the 1950s, landowners planted rows of the huge cactus creating impenetrable living fences.

Most treasured by the Mayo, Yaqui and other native peoples of Sonora is the pitayo’s delicious fruit and the many social events of harvest season. July through September, local people remove fruits using a pole made from an agave or other plant stalk. About the size of golf balls, the fruits are filled with vibrant pink, sweet and juicy flesh. So delicious and in demand, most fruit is eaten fresh after harvesting.

In the not-so-distant past, people in traditional villages dried the fruits or made them into wine. Now that popular beers are readily available, wine making has been mostly abandoned. In dry regions, pitaya fruit pulp could be spread out, dried and eaten later. This practice was especially important in times when food sources were scarce. People don’t rely on pitayas for food now as in the past, but for some, selling fruit in the streets provides a way to support their families.

In Sonora, the main threat to the pitaya is buffelgrass (Cenchrus ciliare) planted on millions of bulldozed acres to feed cattle. Bufflegrass is highly invasive, flammable and one of the greatest threats to desert ecosystems. On the hopeful side, some ranchers may be turning away from buffelgrass and instead planting pitayas as an economic crop.

Biological diversity and cultural diversity influence each other. Just as cactus and other plants adapt to their environments, people adapt and rely on the resources they provide. Perhaps we urban dwellers can appreciate and learn from these examples of interconnectedness and resilience as we celebrate Diversity Month.