In the late 1940s, brothers John and Arthur Earle would run around barefoot exploring their new home: Desert Botanical Garden.

At the time, it was a sprawling 360-acre property (the Garden has 140 acres today) that consisted of Webster Auditorium, a small trail with a couple thousand accessioned plants and its executive director, who lived on the premise. If guests drove to the Garden, they might’ve mistaken it for a desert wasteland. As for kids of today, the Garden could’ve been a nightmare. There were no television, toys, nor other kids to play with. It’s hard to imagine a place like this to be appealing to children — let alone a home.

Yet, the Earle family did just that: Make the Garden their home.

“We were fortunate to grow up here,” said John, 84, who is now a Garden volunteer with his wife Phyllis and lives in Tempe. “All of this area, going around and climbing the top of Barnes Butte, all of Papago Park was our playground.”

The Earle brothers — the children of former Garden Director Emeritus W. Hubert Earle — were the only kids to ever live at the Garden.

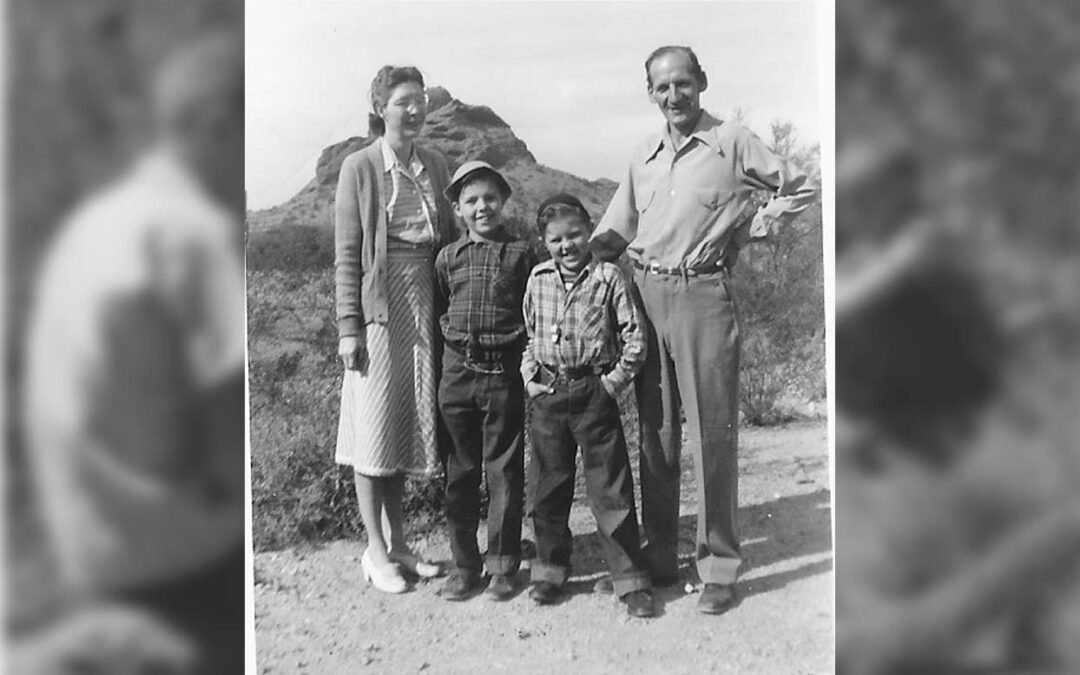

In 1945, the Earle family arrived to Phoenix from northwest Indiana with their silver Liberty trailer and their beloved mutt, Midnight. John and Arthur were 8 and 9 years old, respectively. The family moved after their patriarch, W. Hubert Earle, was diagnosed with severe asthma. His condition was so dire that doctors gave him no more than a few months to live unless he moved to a drier climate, the Earle brothers shared. They first settled in a small community in the Valley, where they had to share washrooms with other families.

But one day in 1947, their lives changed after their father took them to the Garden.

At the Garden, Mr. Earle explained the scientific names of plants, using his extensive knowledge of Latin, to his family. Mr. Earle had no formal education in botany or horticulture, but his skill drew the attention of former Garden Director William Taylor Marshall.

Marshall, who overheard this, was so impressed that he offered Mr. Earle an interview for the onsite gardening position, the Earle brothers said. After World War II, the Garden was ramping up its operations by opening more frequent, adding new plants and tending the area for visitors. All of which required an extra hand.

Mr. Earle landed the job, and with it, a new place to call home. The family stationed their Liberty trailer south of Webster Auditorium, and so began a new adventure for the Earles.

“We didn’t have to share a communal bathroom anymore with any other families,” said Arthur, 86, who is now retired and lives in San Diego County. “That was nice because it (the facilities at the Garden) was ours.”

Although Mr. Earle was the only one on payroll at the Garden, the family helped out in various ways. The boys’ late mother Lois Porter Earle volunteered on weekends to greet guests and collect entry fees (which were 10 cents). She also served as the Garden’s bookkeeper, storekeeper (when the Garden built its first visitor center) and hostess. Her warm smile and kind hospitality made her the unofficial face of the Garden. Throughout the trails, one could find traces of her homey and cozy touch— she cooked Thanksgiving dinners, decorated for the holidays and encouraged guests the importance of conservation of desert plants. All of these traits have inspired a generation of volunteers and staff. In 1972, Garden staff hung up a plaque made in memory of her service inside the herbarium.

“The real gift Mom left with me was being comfortable with the public. Mom was open and welcoming of all people, and dad could get people involved with the Garden,” Arthur said.

John added that his mom “was a very gracious lady … who helped introduce visitors to the Garden.”

Still, living in the desert — at a time when AC units hadn’t yet been mass produced — requires thick skin.

“We used to sleep on cots outside if it got really hot,” John said. The Earles lived in their Liberty trailer until Archer House, named for Garden supporter Lou Ella Archer, was built in 1952.

And although it was an adjustment, the Earle brothers made living in the Garden a cakewalk.

“If you eat a pound of dirt, you have immunity for life,” Arthur said jokingly.

The brothers would run around barefoot, undaunted by the prickly plants, wildlife and rugged terrain. During monsoon rains, they would even play in the water that filled the wash outside of Webster Auditorium. And they hiked Barnes Butte, west of the Garden, so much so that they became experts of its hillsides. The brothers even helped the local sheriff and his team rescue a hiker who was stuck near the top of the butte.

“It was better than boy scout camp,” Arthur said. “We had no neighbors. We were more or less inclined to make our own entertainment.”

Indeed, the brothers resorted to creating their own forms of entertainment. John used to sit on the old wooden table inside Webster Auditorium tinkering with carts, wagons and bikes. Arthur on the other hand was the adventurer and loved to bike around the Garden, including the dirt path that is now Galvin Parkway. Occasionally, the brothers would ring the old bell in the front patio of Webster Auditorium at 5 p.m. each day to notify guests the Garden was closed.

The Earle brothers lived at the Garden from 1947 through 1961— almost their entire childhood. In 1968, the Garden lost its chief volunteer when Mrs. Earle passed away. Mr. Earle continued living in Archer House until the 1970s, and retired in 1976.

After graduating Tempe Union High School, Arthur worked several jobs and saved money to travel through Europe. His appreciation for the natural world and science in general led to a career as a biology teacher.

“Dad influenced me” Arthur said.

But his passion for adventure and the outdoors was what ushered in exciting journeys in his life, including as a park ranger in Alaska, volunteering and working for local chapters of the Sierra Club, sailing down the southern coast of Mexico with friends and a stint at the Point Reyes Bird Observatory in Berkeley, California.

“He can name any bird you can think of,” John said of his brother.

John, on the other hand, had a career in printing before retiring. He met his wife Phyllis, who also grew up in the Valley, and settled for a life in the Valley. Apart from the occasional visit, the couple weren’t very involved with the Garden until volunteer Archer Shelton called them to join as volunteers. Since then, the couple has been part of the Garden, helping in various events and programs, including the semiannual plant sales.

In many ways, the Earle brothers grew up with the Garden — seeing firsthand the addition of new buildings, an expanded plant collection, the creation of new trails, paths and horticultural vistas that remain popular to this day. One of those admired sights is the towering saguaros, organ pipes and other desert plants that sit on the north end of the Butte. (Saguaros typically prefer to grow on the south end of mountains.)

“In the early 60s, dad decided to plant many of these saguaros, organ pipes and barrel cactus on the Butte,” John said. “You can see how much all those plants have grown since then. I think dad’s future thinking was ‘hey, if we put some cactus up there, people will see it on the drive to the Garden.’”

Mr. Earle’s idea remains a success and is one of the Garden’s most iconic backdrops. Today, Ullman Terrace is used to host a variety of experiences because of the breathtaking landscape that fully immerses guests to the natural wonders of the Sonoran Desert. Several of the saguaros Earle planted about six decades ago now stand at a height of more than 20 feet on the Butte.

Hubert Earle’s legacy at the Garden continues to this day. During his tenure here, he started a seed exchange program with several foreign countries. Earle would often correspond with other botanists, scientists and researchers from around the world, sometimes sending a few cactus seeds with his letters.

Even though he didn’t know it at the time, that work manifested into the Garden’s state-of-the-art Ahearn Desert Conservation Laboratory, which houses more than 4,000 seed accessions. The Garden also works in collaboration with The Smithsonian and the North American Orchid Conservation Center to conserve seeds from numerous orchid species of the Southwest.

“Both mom and dad, if they were here, they would be pleased, surprised, honored to have the time and privileged to have worked here,” John said. “They would be awed.”