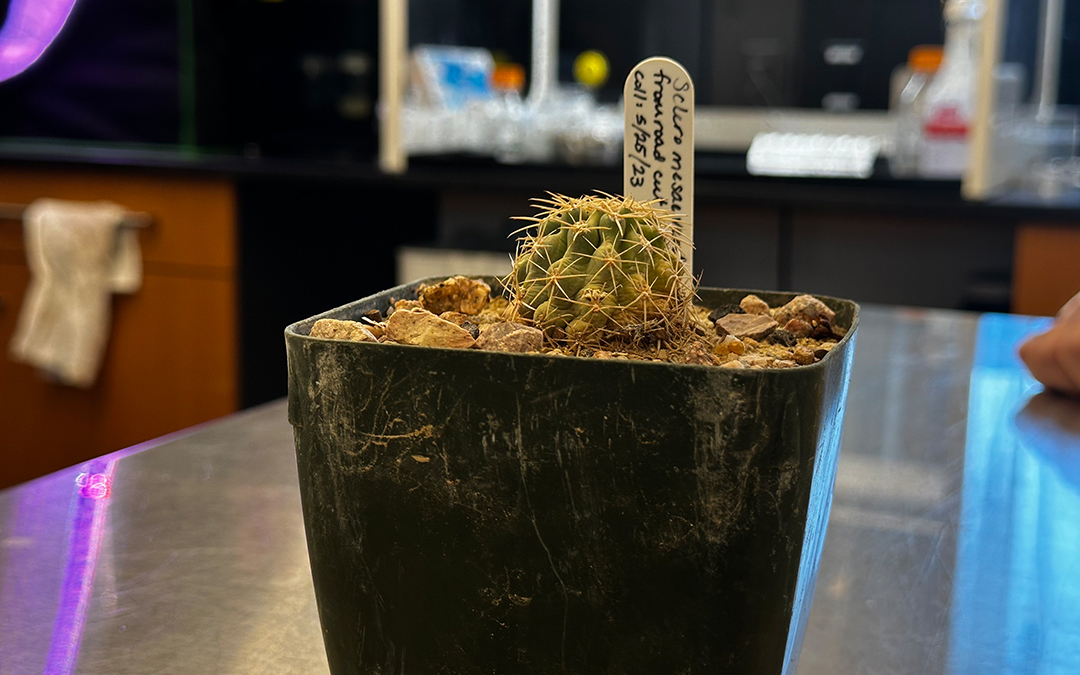

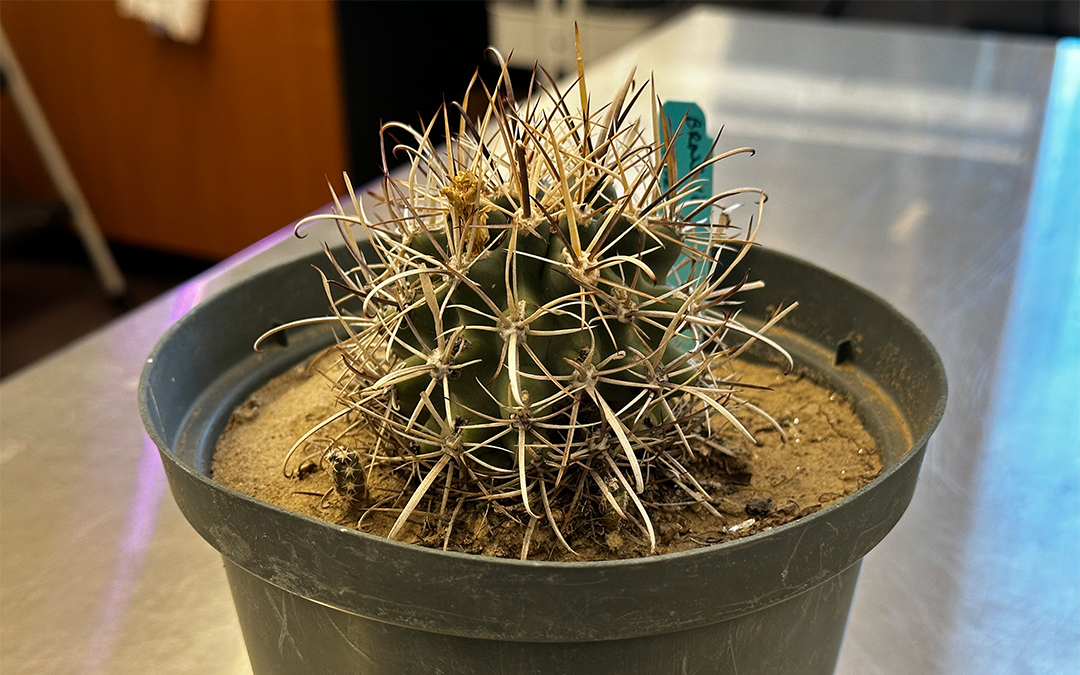

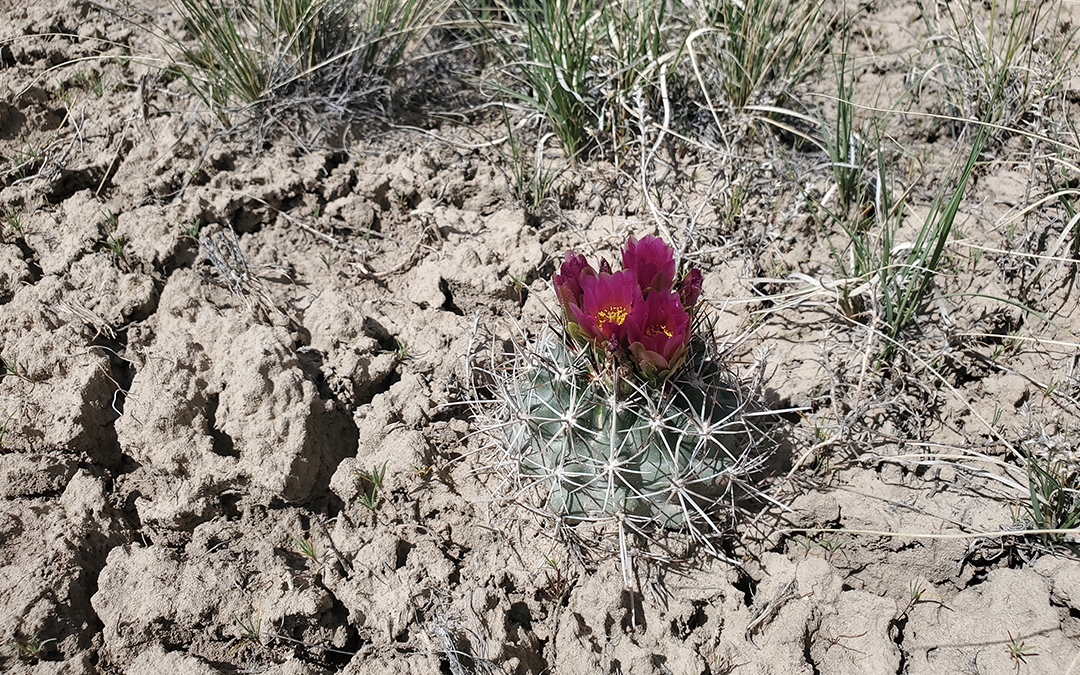

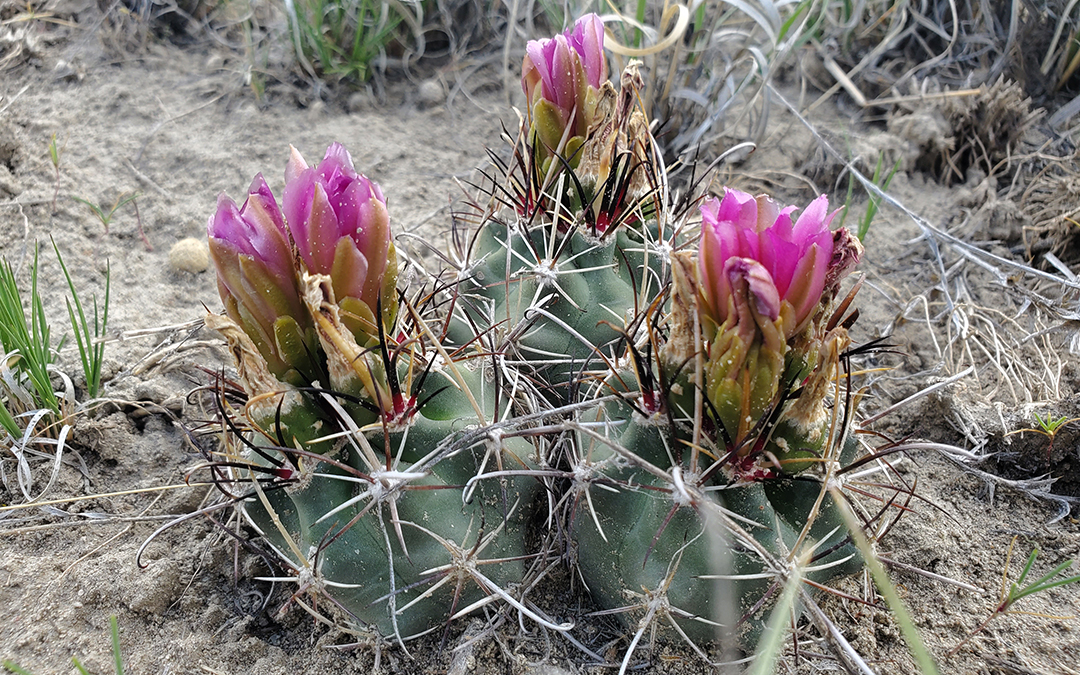

Across the sandy desert floor in northwestern New Mexico, two small rare cactus species — Sclerocactus mesae-verdae and Sclerocactus cloverae — call this place home. Yet, these plants are threatened by poachers and habitat loss due to oil and gas development in the area, both of which have depleted their already low populations numbers in the wild.

Because these plants are tricky to grow, researchers have had a challenge using traditional propagation techniques like seed germination, which require a lot of patience and time — two things conservationists don’t always have.

Desert Botanical Garden researchers are studying the efficacy of a unique propagation method that might help grow these endangered cactus for reintroduction into the wild to increase their already-existing populations.

One of those researchers exploring this practice is Luis Romero, Garden conservation collections research assistant, who started his role in October 2022.

Romero graduated from Arizona State University in 2019 and has a background in microbiology. He has worked at various organizations across the Valley, including as a seasonal gardener for the Garden in 2021, growing mushrooms at Chandler-Gilbert Community College, surveying grasshopper populations in northern Arizona for the U.S. Department of Agriculture and conducting plant tissue culture for a private cannabis company.

And it’s that expertise in tissue culture, otherwise known as micropropagation, that helped Romero land his current role, grant-funded by the Bureau of Land Management of New Mexico, at the Garden.

“I really was able to cut my teeth into tissue culture because we were just producing plants like crazy,” Romero said about his experience at the cannabis company. “We would take diseased plants from clients, clean them up using tissue culture — so getting rid of any pathogens and diseases — grow them out, and then, return the fresh plants material to the client. So, they have a fresh new plant to work with.”

Plant growers and researchers often rely on traditional propagation techniques, like seed germination and cuttings. Numerous cactus species are able to form a whole new plant from a cutting of the parent plant. But these methods can present a challenge when dealing with slow-growers.

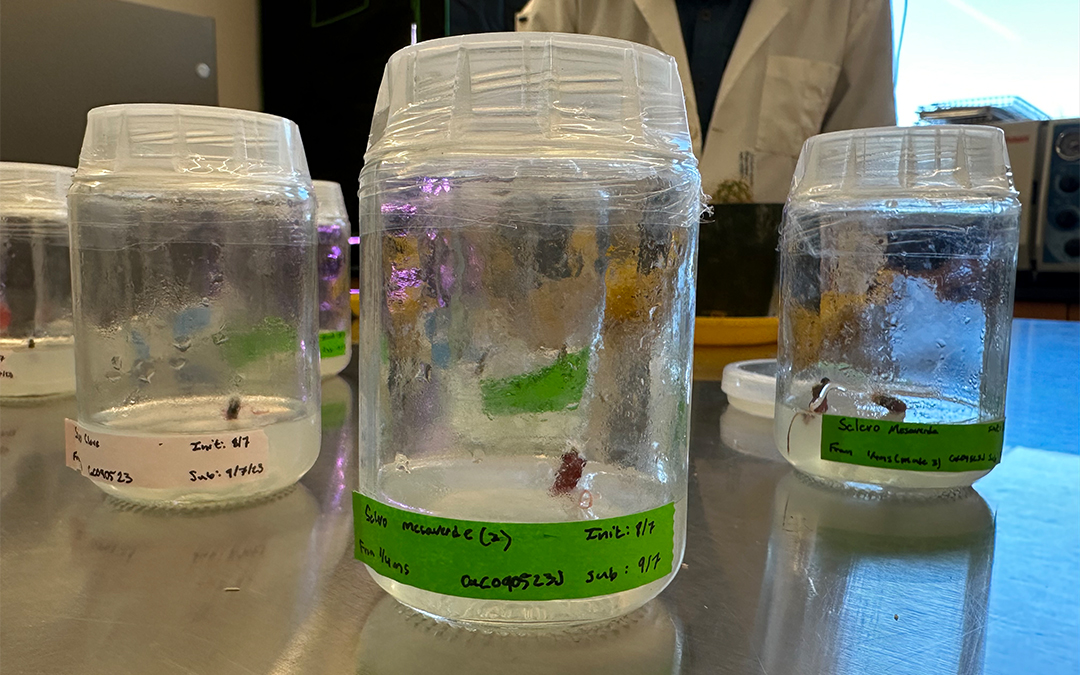

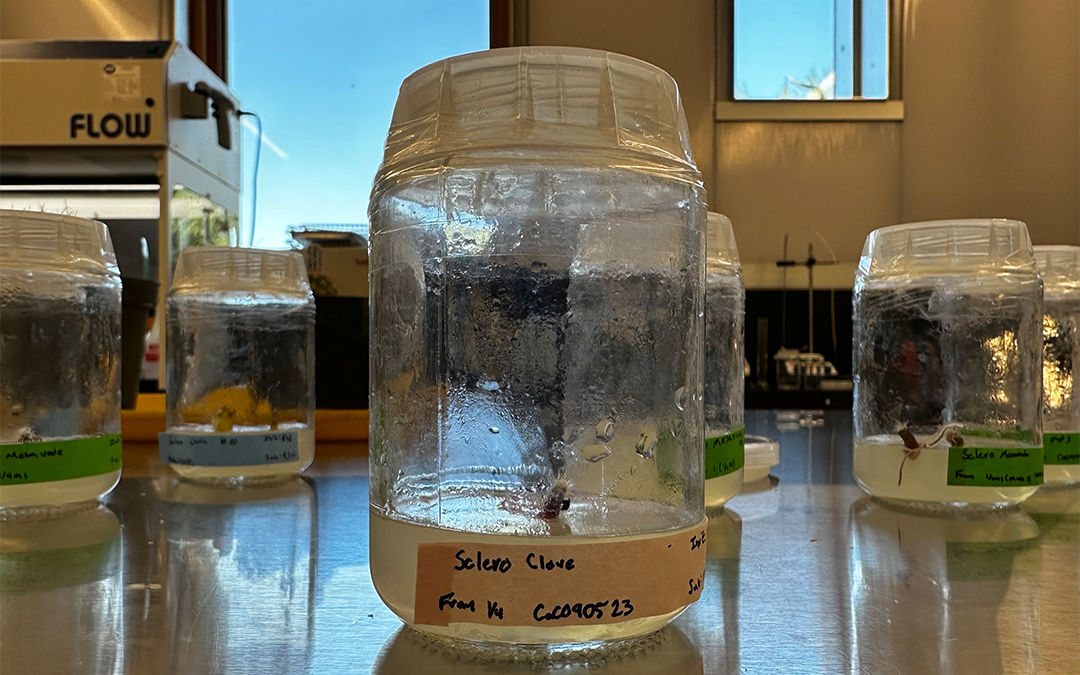

Enter micropropagation. The process involves growing plants in vitro from seeds or cuttings, in a container with a gelatinous substance called agar under sterile conditions. In short, the idea is to produce a large quantity of plants —genetically identical to one another — in a brief amount of time.

“If you placed the plant onto multiplication media, you would induce multiple shoots. From each one of those shoots, you can place onto more media, which in turn produces more shoots. As you see with this exponential process you would have hundreds of plants from a single shoot in a small amount of time — possibly hundreds or thousands of cloned plants in a few months. Where with normal propagation you could produce a similar amount of plants but on a much longer timescale.”

Romero’s main focus is to understand how micropropagation can be utilized in conservation efforts that includes the two Sclerocactus species and the rare Canelo Hills ladies’-tresses orchid (Spiranthes delitescens). The latter of which is being scented out by specially-trained canines in a separate research venture at the Garden.

Although it sounds straightforward to artificially grow plants in jars to help augment their population in the wild, Romero faces several challenges shepherding this method on Southwestern cactus that very few scientists have worked on before.

The first challenge is making sure the plant can grow in culture. Sometimes there might not be enough seeds, plant cuttings or a live plant to work with. In the case with the Sclerocactus species, the seeds and tubercle cuttings weren’t producing the best results — often creating mutations on the plant or failing to grow in the jars. So, Romero performed embryo excision, a process that involves removing the seed coating and transferring the embryo onto the media to get the plant to grow. Another challenge is making sure the plant grows in the media, or the nutrient-rich substance inside the jars. Each plant requires a unique formula, or recipe, that enables it to grow effectively. Since there is not enough information on how to prepare media for these endangered plants, Romero has had to research recipes that work best for the plants. And if the plant is able to produce roots and continue to grow, Romero has another challenge: transitioning the plant from the jars onto pots. It’s still very early on in his research, but some plants have the possibility of dying during this stage. And the final hurdle is getting those potted plants established in their final environment.

“There’s a few hurdles with this kind of work,” he said.

“It did take me a lot of trials and experimentation, especially with the Sclerocactus, because there’s not a lot of literature written about how to tissue culture them,” Romero said. “There’s a lot of research and development going into this.”

Still, Romero is not the type to give up. After many trials, he has a few Sclerocactus, as small as a few centimeters, growing in jars via micropropagation.

In addition to using these plants for on-the-ground conservation efforts, tissue culture could also be used to produce large numbers of rare cactus species that could be sold to the public to help reduce the illegal collection of these plants from the wild.

“There’s a lot of cactus poaching, especially with these more rare and endangered species. And a lot of these populations are getting wiped out,” Romero said. “But if we’re able to produce more of these rare and endangered plants, we are able to sell them and reduce black market incentives to poach the cactus from the wild.”